A few years ago during university in California, out of sheer curiosity, I picked up a book geared toward young audiences: Sally Ride: A Photobiography of America’s Pioneering Woman in Space, which is relatively easy to absorb and remember, visually. It is no stretch of the imagination to say that the titular woman is a household name in the US public consciousness, even if people know very little beyond her famed title as the first US woman in space; at the time, I was one of those people. The end of the book reveals its more personal angle, informing readers that Dr. Sally Ride, was, in fact, the life partner of the book’s author, professional tennis player turned science educator Dr. Tam O’Shaughnessy.

That was the first time I had learned about their relationship, which was kept a secret from the public until Ride’s passing in 2012. After I graduated, my alma mater renamed the dormitory (then named for Spanish colonial missionary Junípero Serra, whose identity from which the university has now sought to distance itself) neighbouring my first-year home after Ride, given that she is amongst the ranks of famed alumni, having received a bachelor’s in physics and another in English, a master’s degree in physics, and a PhD in physics from the university. This was simply a very symbolic gesture, but thus it made sense why O’Shaughnessy’s photobiography was sitting on a “featured books” shelf at the library. However, it was a wonder that I wasn’t previously aware of their relationship, especially in an era that champions queer “heroes” and role models (sometimes performatively). There are arguably multiple intersecting reasons why this is the case—amongst them, the timing of the public acknowledgement (fewer than 10 years before) as well as an eagerness to keep science “untainted” from external influences, an objective that is blatantly impossible but still wholeheartedly believed in.

In a press conference before she became the first US woman in space, a reporter suggested to Ride that she would be relegated to a footnote in history. The accomplished mission specialist-in-training brushed this off with a laugh, one among many of iconic moments in her obsessively publicised and scrutinised career as an astronaut—well, a woman astronaut, as the perhaps shockingly (or not) regressive media at the time insisted on specifying. What has instead become that footnote could very well be Ride’s 27-year life partnership with O’Shaughnessy. Like the aforementioned book, there have been pieces of media that have sought to highlight Ride holistically. A new National Geographic documentary by investigative journalist turned Emmy-nominated documentarian Cristina Costantini, simply titled Sally, intends to continue morphing that footnote into a full chapter: after world-premiering at Sundance, it travelled to True/False Film Festival and then South by Southwest (SXSW).

What is unique about this new film are the accounts from O’Shaughnessy about the life of the two together, which make up a significant portion of the film, primarily through talking head interviews. These fill gaps and raise important questions about the documentary form as well as, perhaps more crucially, how we treat one’s legacy when it is entrusted to someone else. Several valid criticisms have emerged that question Costantini’s approach to the film as going against a reconstruction of Ride’s life philosophy, which was very private in aspects beyond that of her romantic relationship. Conversely, the film seeks to present a very wide-ranging look at her life, and one might even go as far as asking whether she would have wanted to a work like this to be made.

However, we aren’t making the decisions, and we certainly aren’t the arbiters of her life history. Sally also includes chunks of voiceover from Ride herself, which are very effectively edited to act as pieces of narration, so it is not as if O’Shaughnessy is the only person contributing to the narrative-making. A crucial piece of this argument comes in the final moments of the film, in which O’Shaughnessy recounts asking Ride how she wished to mention the nature of their relationship for her public obituary. Ride is stated as having left it up to her partner to decide. Namely, in a deep but understandable act of faith, she trusted her life partner to make that decision, knowing that whatever she chose would outlive her, in a manner that would eventually become uncontrollable. Latter parts of her obituary thus read, “Dr. Ride is survived by her partner of 27 years, Tam O’Shaughnessy…”, a fanfare-free 12 words that opened a massive Pandora’s box, despite the fact that they were simply a queer couple existing in their own right.

Credit: NASA

Credit: NASA

In the film, O’Shaughnessy doesn’t hide her own frustration regarding their secret relationship, while Ride didn’t seem to mind. It is thus understandable why she personally plays such a large part in Sally as an interviewee; her accounts could be heavily depersonalised and read back as narration, for instance, but this would likely further disrespect their relationship. If the astronaut entrusted her partner with how they together were defined after her passing, it is no stretch of the imagination to think that she would have also agreed for O’Shaughnessy to further define her legacy in other forms—even though, yes, it is still just conjecture.

Like most documentaries, Sally places the burden of trust on the viewer, requiring the audience to believe in what’s being shown or narrated before them. The sensitive aspect is, of course, that it is about her very private personal life, where some, well-intentioned, try to come to the defence of Ride. Nonetheless, it becomes a disservice to engage in a sort of truth-seeking behaviour about the scientist’s wishes. To doubt O’Shaughnessy’s ability to tell Ride’s story is to sever that connection between them as a couple. A healthy, critical dose of scepticism is always necessary, but it is also worth questioning the origins of such scepticism. Is it coming from the fact that Ride’s partner outlived her and is now the one who is best suited to tell her story? Or is it coming from the act of film creation itself as a subjective medium?

Asking about O’Shaughnessy’s intentionality or perspective is a slippery slope world where filmmakers make personal stories about family archives, but a partner’s truthfulness is interrogated because of gaps in information that were explicitly withheld as a personal choice and out of safety. Specifically, these are partners whose connection was never institutionally recognised within Ride’s lifetime, which somehow seems to have a subconscious effect on how we view O’Shaughnessy’s narrativisation. The film discusses how, in 2001, the two founded the science education company (now a non-profit) Sally Ride Science, which O’Shaughnessy runs as executive director. To relegate her involvement in telling Ride’s story as one that is self-serving creeps into territories of disrespect toward the couple’s more than quarter-decade together.

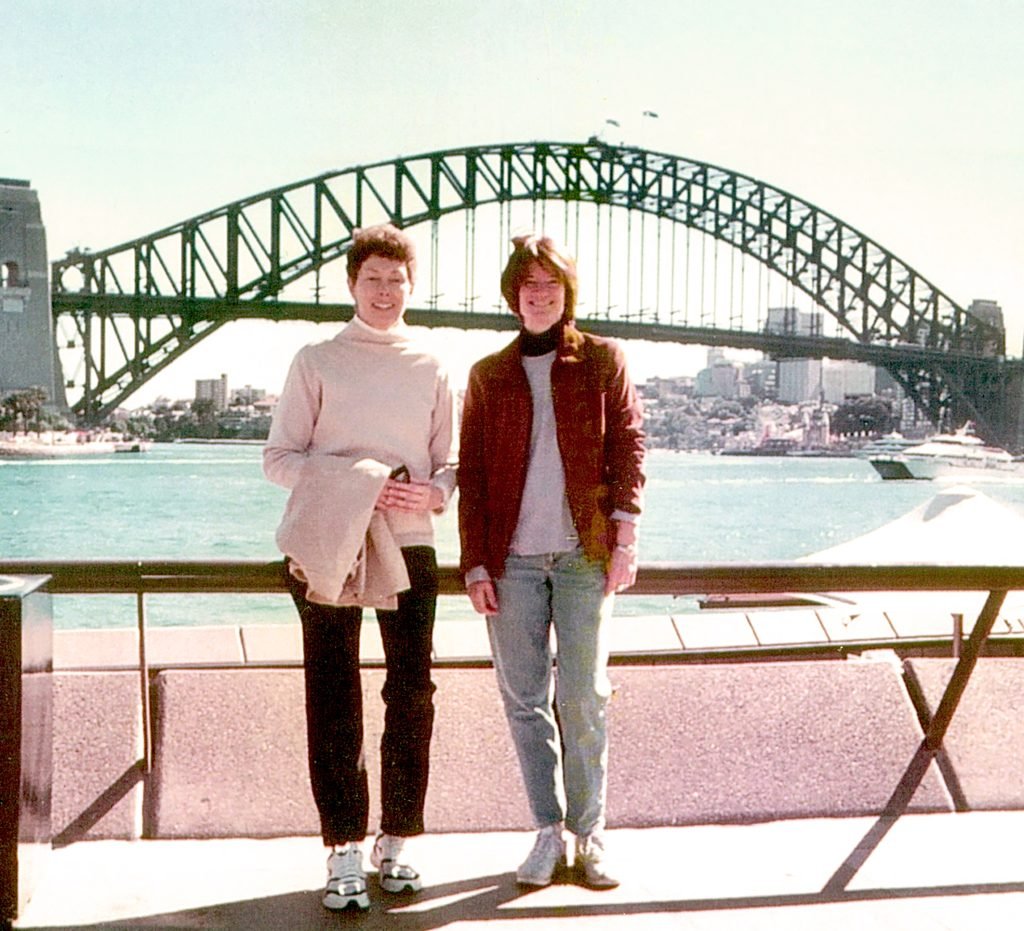

(Courtesy of Tam O’Shaughnessy)

Ride’s life has been subject to plenty of history-making in other ways, which are seen as more trusted and objective, despite them being removed from a personal angle, often of deep importance to queer people. She has an institutional, state-cemented legacy, including commemoration in a new series of quarters dedicated to “historic contributions of twenty trailblazing American women” and President Obama’s presentation of a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom to Ride in 2013, accepted by O’Shaughnessy on her behalf. (It’s worth pointing out that this was a posthumous award given 10 months after Ride’s death—our institutions are only catching up to the achievements of queer people after they have passed.)

History is seen as objective, cut-and-dry, and only “real” when typically verifiable through written sources—as consumers, we don’t know how to react when information is out of this rationalisable realm. However, it must be noted that written history is not the only valid form of memory. Oral histories from cultures without traditions of written history are only more recently being recognised as equally “true”. In Sally, O’Shaughnessy does read from and present a cheeky handwritten letter from Ride, which is an immensely touching moment; likewise, there are a few archival photos of them together, but few are presented. LGBTQIA+ individuals and communities have historically had to hide for fear of backlash; to expect a bookshelf of journals, memoirs, or notes that lays out history as we think it stands—and also to expect it to be fully substantiated for us is, frankly, naïve.

There are other ways to be remembered, which are seen as inferior forms of documentation that are actually gaining increasing importance—for instance, social and digital media. This is a realm in which Ride’s cultural legacy lives on in ways likely unheard of by a wide swath of the US populace. The famous TikTok meme song about NASA asking a woman astronaut whether 100 tampons for under a week in space—yes, that song—was about Sally Ride’s first mission in space on the STS-7 mission, but it never calls out the scientist by name. Costantini recognises this moment (sans meme) by going on to highlight how NASA designed a makeup kit for her to use in space, a hilariously misguided moment that could now be read as unconscious misogyny, even if it was well-intentioned. It’s arguable that her legacy as perpetuated in this manner is bound to have a profound and lasting impact: social media is where chronically online young people reside, where emotionally affecting stories are transmitted quickly, and also where niche topics thrive, allowing for the formation of dedicated communities. One of the most iconic archival moments in Sally is of Ride curtly informing a reporter that they can call her Dr. Ride or Sally—but never “Miss Ride”, something that would do the rounds online if it were a video taken today.

Costantini uses warm, hazy action-oriented reenactments (with cinematography by Michael Latham, known for The Assistant and The Royal Hotel) to emulate personal moments as described by O’Shaughnessy—such as a recollection of Ride when she first expressed romantic interest—which is sometimes considered a fraught choice in the documentary form. However, the director never tries to pass them off as archival footage, instead using aspect ratio shifts and vignetting to indicate when scenes are reenacted or historical footage and photos are inserted without being intrusive toward the viewer. The reenactments further allow for our delusions to be shattered: it’s one thing to hear about a romantic relationship that we never witness and can thus displace to the peripheries of memory, but it’s another for it to be transformed from thought to image that we must confront. The choice between the director (aided by O’Shaughnessy’s accounts) to use two actors to reenact a passionate moment between the couple, which eventually alludes to a sexual encounter, is a resolute statement in and of itself.

Most successfully, Sally doesn’t shy away from the intertwinement of Ride’s scientific life with her personal one, even if the former was so aggressively in the public eye, and the latter was the polar opposite. Today, this is a more-than-necessary stance to take in a world that actively seeks to pretend we live in a pure meritocracy entirely divorced from historical influence. There will always be people asking how specifying gender or sexuality pertains to a discussion of her accomplishments (“Why can’t she be just a scientist?” one might shout), and Ride herself intentionally detached aspects of her personal life from her identity as a scientist. But if we look at Sally, we can plainly see how it does matter, as the film reveals the immense misogyny that Ride endured while in four years of astronaut training, largely from the press. If the goal is to engage in holistic history-making, then seeing Ride as all of who she was is of crucial importance, as Costantini sets out to do.