This month, their animation could be found in a gallery exhibition space in Greenwich. Previously, it has accompanied live music performances. You, the reader, can watch it on YouTube.

More than offering escape from grief, displacement, or chronic exhaustion, Into the Next Tide insists that joy is the very substance that carries us through them. Joy is rendered here as a checkpoint, as somatic memory, and as a radical continuity.

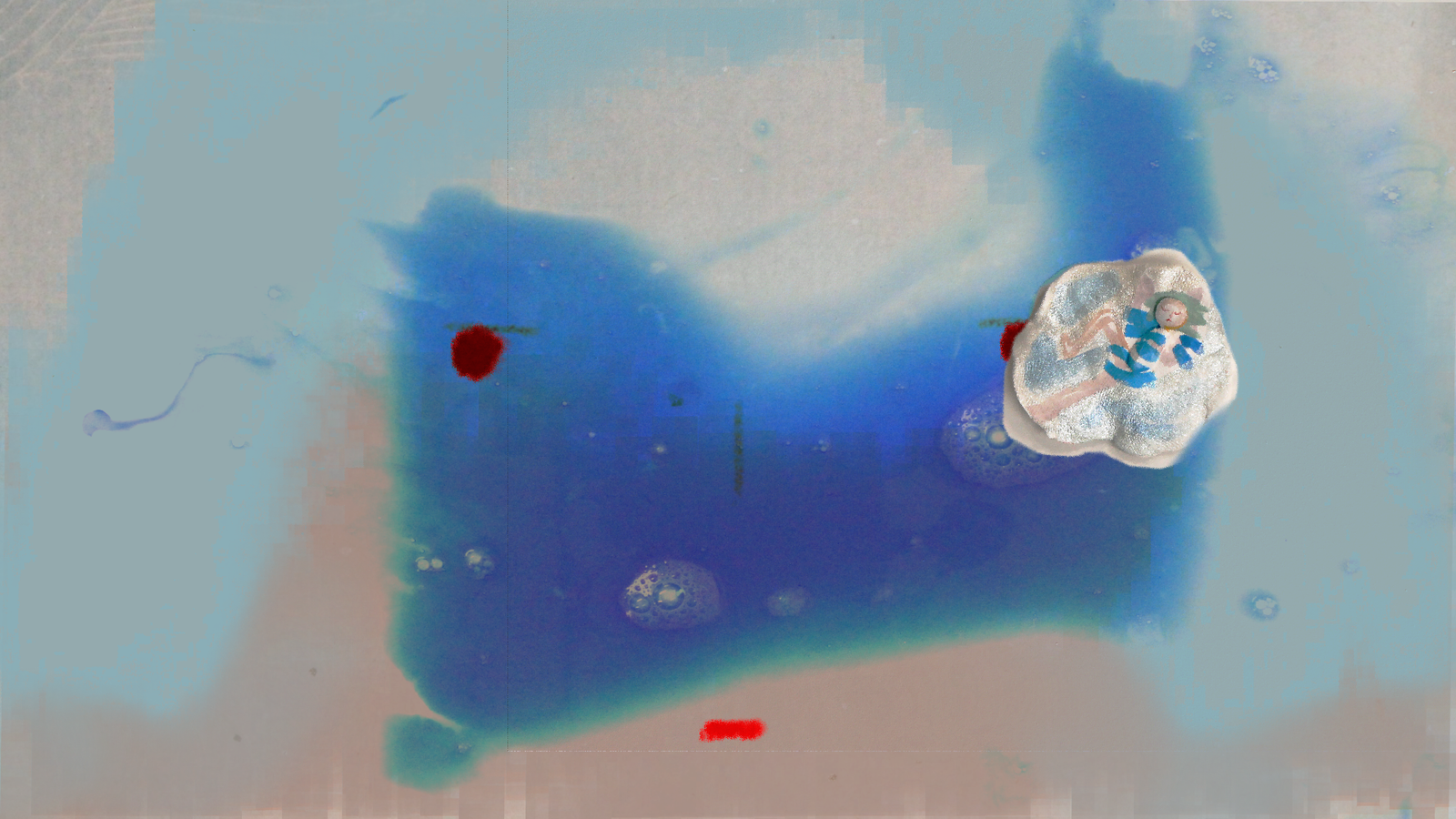

Watercolour, animation, and installation intermingle, refusing containment as the images ebb and flow like the tide. Each scene functions as a kind of “mini-ecodome” saturated with emotional resonance, which together form an oceanic whole of interconnected fragments. By refusing linearity, the looping narrative structure creates an emotional rhythm closer to breathing or tidal movement.

Into the Next Tide resists confinement to the single-channel screen. It has lived as a gallery installation, a canal-side projection, a performance with live music, and a festival screening, with each site shaping how audiences encounter it. This adaptability reflects the artist’s broader practice of decentralizing cinema—moving away from fixed institutional contexts and instead inviting porous, participatory encounters.

Just as important is the way abstraction in the film speaks beyond language—gestures of colour, rhythm, and movement articulate what cannot be reduced to words: the film functions as a living conversation: it changes in meaning with each viewing, unfolding differently across contexts, audiences, and even for the artist themself. Into the Next Tide thus positions art not as a fixed statement, but as a dialogue—a tidal exchange between body and memory, grief and joy, artist and audience, self and collective.

Yaya is a London-based artist and creative spaces facilitator, whose practice spans animated film, painting, and performance art – all drawing inspiration from the community landscape of queer and trans spaces in the capital. Their work reflects themes of belonging, survival and grief, and centres building reciprocity in our relationships with outdoor spaces and learning from cycles of nature.

With their animated work being so fluid, it feels appropriate to extend and extrapolate Yaya’s short into a freeform interview, exploring the personal, queer, and cultural contexts that have birthed their intriguing and poignant piece of mixed-media animation.

*****

I’d like to start by asking about the short-form nature of the work, and how that relates to memory for you. Did the transformation of your personal memory to this form come naturally to you?

Yaya Xi-lin Wang: The piece is a recovery of memories after upheaval. I like to perceive it as a journaling process, maybe a grief journal. There is a non-linear quality to making it. And this applies to the duration as well.

What was the concept that sparked this project? How would you encapsulate your logline and your intent?

The logline is about a new start: what are you leaving behind, what will you keep carrying. What ends with you and what will start with you. When writing it, I thought of a kind of seedling that’s about to find out what’s next.

Did you have the full structure in mind from the start of your process, or did this piece emerge and evolve in fragments?

I didn’t have a full structure in mind at all. Because the making was treated as more of a performance itself – a free-spirited art piece – there was a lot of freedom for me to not work with tools more traditionally associated with the film industry, such as a script, a storyboard or planning with team-tasks to pass-on. This is an artist’s film, where each scene is an object, a mini-ecodome of somatic memories and inputs, and they all come together as fragments of a bigger piece. There is something ephemeral about their duration. In a way, each scene of the film could be durational, especially when I think of them as spatial installations, because they’ve been made with that intent. Each and every single shot is its own whole universe of a memory.

What materials are used here in the animation and beyond? There’s a mixed-media element.

I like water-based mediums because of the improvisational aspect of them. It goes back to what I said about discovery – because everything is conversational and you partake in not-knowing yet committing to being in relation in the forming-the-connection. I like to think of watercolors as the tides of the oceans pushing my boat towards the next destination.

Do you view cinema as psychologically escapist, or as a site of introspection?

Installation, interactive, participatory, invitational. I long to hear more about internal stories, the soma, the inner-migrations and displacements – our bodies are a microcosm of the collective body of the Earth, our different selves, different parts and voices, all in relationship, in community, in rupture, in conflict, in ancestral lineages and longing for connection. I want to hear more stories and histories of re-pair-ing, from the soma to the bigger scale of us.

What animation shaped your own understanding of the medium? Would you say that your approach here is more shaped by influence or instinct?

Working as a watercolor technician on Genius Loci (2020) shaped a lot of my understanding of slowness and intentionality in achieving a picture. Each single image of an animated piece goes through such a level of care in its making. Painting frames of Genius Loci was truly humbling, and healed a lot of my relationship to productivity and practicality, for it being a set on which care was always given priority.

Shinji Hashimoto, who animated the running-away scene in The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, inspired a lot of how I care about texture and honoring the “painted” feel in my animated work. Because I’m a painter as well, it can feel like betraying my brushstrokes when I have to trade looks away for efficiency. There is a lot of bargaining in animation – which is part of the play! And something deeply satisfying when you win, and have made room for the looks that you want yet the images are moving with abundant generosity.

Tell me about the wonderful original score. The way it unfurls feels like a throughline and a guiding light through the film.

Yuki (aka Mer Sounds) and I have this relationship that is very quiet and not always verbal. When we spend time together we literally don’t have much to say to each other! But we deeply witness each other even in our quietness, and that happens the most magically and potently when we merge music and moving images together. So much of our collaboration has been improvisational, because it just works. We either say Yuki makes the sounds first and I animate on top, or I make my animations and Yuki adds onto them later. We’ve also created some of the sounds together by playing with the seashells used in the film, in a bowl of water and a recorder. Yuki bridges the gap where the words fail me, and is by definition a sonic guide into my animations.

Tell me about the use of bilingual intertitles.

From not having a mother tongue to being neurodivergent and often only semi-verbal, I always feel like there’s a transaction fee that applies in language, from my heart to my actual words. But at the time, using intertitles still felt like a worthy attempt at communication. Healing and recovery are very much conversational; therefore, half of it, you don’t know the outcome until dialogue happens. And I wanted to do my part of the dialogue with two languages that I know the other participant of the conversation might understand.

Figures and physical forms are constantly in flux in this film. Do you find that animation is an intrinsically queer way to explore the body and self?

The motion reminds me of drawing a map, tracing your way back towards something. And my work often feels like I’m finding small checkpoints, somatic trails left by the queer ancestors that came before me – I’ve learnt from their resilience since a young age and from elders, but more recently, I’ve learnt from their joy through the joys that my own body allows me to experience. Sowing queer joy might just be more potent than any story of being a ruthless warrior – not that I’m not – but because joy is what will sustain the fire, feed the communities, hold you through the next hardship in a couple of weeks, a few years or the next lifetime or the life of your descendants. Our radical futures must be made of joy.

If anything defines these figures, it’s the use of block colour on each at points. Could you elaborate on your thinking behind your use of colour?

Colours are forces of nature. Sky blue sea water, end of a sunrise, deeper part of a forest, morning glory, restrained sunset orange, summery grassfield. I like to think that I’m borrowing wisdom from different colors in different scenes, and actions of characters or landscapes. There is a poetry in real life where colors we see actually translate to what we don’t see, the moment the light reaches our eyes. I like that relational dynamic and try to keep the symbolic of the colors not explained, but there to inform of something unseen.

Tell me about your relationship to land and to water, both in your own self and in this film? Which do you find more grounding?

I want to answer that by drawing a connection back to the watercolour medium. Water carries such a large chunk of my work, because the ocean tides feel like a force of nature, pushing me towards an unknown new place. When I paint, I feel like I’m simply embarking on a little boat and migrating somewhere. My body is the boat and it holds me and keeps me safe but is also surrounded by the immensity and ancientness of the Ocean, a body that carries the oldest memories we could ever access and it is way beyond what verbal communication can do. I feel like it is a rite of passage in learning to trust and listen.

How important to you is the physical site that this work is exhibited within? It’s an interesting element that expands the dimensions within which your otherwise flat-screen work exists.

It feels very important for me that people can get to encounter Into the next tide as a spatial experience – whether it is with the canal under a London bridge, or a physical installation where they can interact and touch the seashells that were part of the film. Because the film is a vessel of somatic explorations, I feel the invitation to play, and exploration can only extend if there is a physical element to it. Which is why I am grateful for the openness and mixed-medium quality of this piece, and how it’s been outside of cinemas so much, in various forms of exhibition spaces and even as part of live-music performances.

What did you discover through making this film?

Fragmentation works like tiny islands and many selves displaced in the soma. I like the idea that the inner migrations are relational and cosmic mirrors of what’s going on in the bigger collective body of the Earth – in relationships, conflicts, survival. Wholeness is already and always there, but so is movement. And we don’t control all of the outcomes by ourselves, because everything is conversational by nature, and involves more than just one self.

Two years later, when I watch the film, I feel like it is conversing with me in a new light. It made me discover how dedicated I am as a person —child-me is not very deep and only craves easy things, simple joys. Adult-Artist-Me is dedicated to creating a future where Child-Me can have an easy time. Those two are also two islands in conversation, and an archipelago to come with the bridge that I’m trying to build between them.

In the future, I’d like to explore rupture and repair (aka re-pair-ing) in greater depth. Conflict happens often with misused power, and I truly believe none of us are above that — especially for those of us who have multiply-marginalised identities yet also privileges, the relationship to whether we have power under or over a situation can often be blurry, complex, demanding us to hold our own otherness and that of the other people involved.

And what would you like your audiences to discover through watching it?

It feels like letting go of a bottled-message in the sea, and a very liberating process. Exhibiting my art is in a way a softening yet a challenge for my nervous system, because it’s telling me that “This is out of your control now”. It is very transformative, sometimes uncomfortable, but it is what I want. Everything is relational, aka conversational. I feel like by making the film and putting it out there, I’m doing my part of the communication. I love hearing back from my audience and being surprised by their unique experience of my film.

*****

Into the next tide was presented at the Queer Migrations Festival from July 19th to August 9th as part of the visual art exhibition at the Firepit Gallery in Greenwich, London.