Writer-director Jun Li’s Queerpanorama (2025) is episodic, consisting almost entirely of a series of a young man’s encounters with other men in Hong Kong. Li’s third feature film became one of a wide variety of LGBTQIA+ projects in this year’s Berlinale, which most recently world-premiered in the festival’s famed festival-favourite Panorama sidebar. The protagonist (a slim, luscious-haired, and soft-featured Jayden Cheung) is referred to in the credits as “I”, a clever shift of perspective to the first-person; the filmmaker encourages us to find ourselves in him, too. But while all of the encounters begin as sexual ones, they quickly expand beyond this nature, often inspires philosophising between the two men—sometimes trite, other times reflective—about the world around them. I meets with men of different ages and from different places, many of them transplants to Hong Kong, all meeting in that very urban metropolis, including young Iranian man Erfan (Erfan Shekarriz) and the older German man Phillip (Sebastian Soukup). Despite their differences, he is always able to connect, whether it be through bodies or words. (This concept is discussed further in our interview with the director and star at the time of the film’s premiere.)

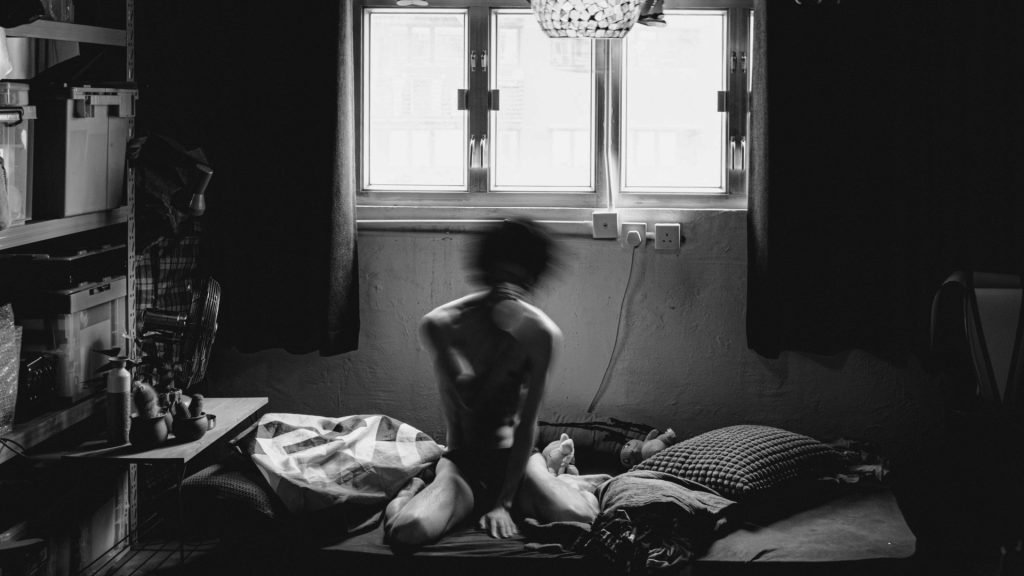

Queerpanorama frames I’s quirk as taking on the identity of those he has had sex with previously, which he does to some extent, often limited to name and profession as he discloses to his next hookup that he passes off as his own. He does little beyond this, such as adopting other character traits, other than instances of either smoking or not smoking, depending on the previous intimate encounter. I changes between being a sexual top or bottom depending on the interaction (whether this is actually just a part of his adoption of other people’s traits is unknown)—a small, but refreshingly stereotype-breaking move on the part of Li, given much representation of gay men on screen. And gratefully, Li doesn’t leave I as an empty shell: while he appears calm and facially emotionless in most encounters, like he is putting up a protective façade, we see spots of emotion that emerge. The filmmaker features a few instances where we witness I dancing alone in his messy flat and singing into a hairdryer in a solo karaoke session. He does have a personality, after all, even if it is seemingly filled with an overwhelming sense of isolation. At one moment, we find him lying in a back alley nearly naked; during another, he is quite literally washed up on the beach, completely nude. But still, I is unperturbed, as if this is the deserving aftermath of such an encounter. To go out and do it all over again is simply part of finding something out there from the world that can never be found.

From the start, Queerpanorama’s sex scenes are explicit but without any fanfare or romanticisation, shot in the same manner as scenes of I talking with his next partner. Li strongly favours long-take static shots at a distance, simply leaving the camera in one place and letting scenes play out, often for entire conversations. Angular jawlines and lush curves are chiseled out in DoP Ho Yuk Fai’s beautiful black-and-white lensing that makes the film feel like Li knows how to make use of the intricacies of grey tones and the textures that make the black-and-white visuals interesting. Distractions fall away, leaving just the movement of bodies and the dialogue between each pairing as the centre of attention.

Despite its simple yet effective approach, the only primary issue deriving from this visual style is that it is deeply unforgiving when it comes to performances. Here, the filmmaker cannot use more traditional montage and editing techniques to hide any awkwardness in staging or dialogue that emerges. As such, the film’s greatest stumbling block is the slightly blocky sensibility to line delivery—which, at times, feels over-rehearsed. The long takes leave everything open and bare: awkward silences must be preserved, while a rushed and bland response is, similarly, stuck as it is. This creates a staged feel to many of the scenes that otherwise are meant to be spontaneous: a post-sex meal, a first encounter, a one-night stand.

While this frustrating aspect continues throughout the film, Queerpanorama offers a remarkable lot by way of its other formal approaches to both style and content. The film’s most curious identifying feature is the repeated use of words and ideas across completely disparate interactions, as if the main character is experiencing déjà vu—and we, too, are experiencing it along with him. Mentions of an open window (the German word “hörnchen”, says the protagonist, sounds like the Cantonese phrase “to close the window”, while earlier in the film I asks if he can open the window), or the particular verbiage of the word “rape” (“My teacher raped me,” admits one lover, while another Mandarin-speaking man begs I, in English, to “rape [him]”, which immediately turns off our protagonist).

With this, Li doesn’t stop at the over-played idea that communication and connection exist across people and cultures (but yes, I speaks Mandarin, Cantonese, and English in the film, although English becomes the lingua franca for most interactions). In Hong Kong’s vast and isolating urban landscape, pockets of intimacy require immense vulnerability, but not exclusively. With Queerpanorama, the filmmaker lightly steps into the boundary region of translation, raising questions about how we use our bodies and words to translate across spaces of the unknown. In a world that relies most often on the spoken and written word, perhaps trusted and mutually consenting corporeal encounters provide a respite. Perhaps they are instead the most secure way to communicate with another human through an altenate form of understanding. From there, we can begin to comprehend.